Niger J Paed 2016; 43 (1):30 – 33

ORIGINAL

Ocheke OI

The febrile child: how frequent

John CC,

Ogbe P,

should we investigate for urinary

Donli A,

tract infection

Oguche S

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njp.v43i1.6

Accepted: 3rd August 2015

Abstract :

Background: Febrile

where necessary: blood film for

illness in children remains the

malarial parasite identification and

Ocheke OI (

)

most common cause of emer-

count, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

John CC, Ogbe P, Donli A, Oguche S

gency room visit. In many tropical

analysis and chest X-ray.

Department of Paediatrics,

Jos

University Teaching Hospital

countries where malaria is en-

Results: Of

the 303

children 180

P.

M. B 2076, Jos, Nigeria

demic, children presenting with

(59.4%) were males and 123 were

Email: ieocheke@yahoo.com

fever are treated for malaria pre-

females (40.6%). The mean age

sumptuously. Current evidence

was 21.7±14.0months, 54.5% were

suggests however that malarial

less than 24months.

parasitaemia in febrile children is

ARI accounted for 44.6% (mainly

declining and the prevalence of

tonsillitis, 61%, pneumonia, 27%

other causes of fever apparently

and otitis media, 12%), while ma-

on

the increase. Therefore, high-

laria and UTI were observed in

lighting such causes of fever as

38.3% and 4.6% respectively.

urinary tract infection (UTI) is

Five (35.7%) patients with UTI

indispensable. This is much so as

were males while 9 (64.3%) were

UTI not only is common in

females. Their combined mean age

younger children and often ne-

was 25.4±18.6months, 57% of

glected but also associated with

these children were less than 24

long term complications

months old. In 3(21.4%), UTI co-

Methods:

Children

aged

6-

existed with malaria.

59months with fever of less than

Conclusions: Acute

respiratory

2weeks were consecutively re-

infection, malaria and UTI are the

cruited. Each child had both clini-

three leading causes of fever in

cal evaluation and preliminary

children under 5 years.

laboratory assessment such as

dipstick urinalysis. Further micro-

Keywords: Fever,

Children, Acute

biological

and

radiological

respiratory infection, Malaria,

evaluations

were

performed

UTI.

Introduction

malaria parasitaemia accounted for only 35 % of 5,217

children presenting with fever.

8

Febrile illness represents the most common cause of

The pre-treatment identification of malaria parasites in a

hospital visits and admission in children globally.

1,2

The

suspected case is beneficial in many ways much as only

underlying causes are predominantly infectious and UTI

individuals with the infection are treated. A new prob-

is

increasingly recognised as an important cause. Ap-

3

lem as a result of this step however is, what appropriate

proximately two decades ago, it was noted that 30% of

treatment would those who test negative for

Plasmo-

outpatient and 50% of inpatient children under the age

dium falciparum parasites

receive, particularly at

the

of

five years living in Sub-Saharan Africa had malaria.

4

first and secondary-level health facilities. Available evi-

Without a reliable case definition, children presenting

dence suggests that with the decrease in the use of anti-

with febrile illness in most cases were treated presump-

malarials, there has been a corresponding increase in the

tively for malaria.

1,5-6

Current evidence suggests how-

indiscriminate use of antibiotics in febrile children.

9,10

ever that there is declining malarial transmission in

Many times, the choice of antibiotics and their dosages

many of the malarious countries in Africa. This necessi-

are inappropriate, inadequate and unnecessary. This

tated the World Health Organisation (WHO), point-of-

practice can lead to increase in the development of sev-

care rapid diagnostic test which ensures that all children

eral resistant microbial strains. It could also lead to poor

presenting with fever are tested for malaria before em-

care and missed diagnosis of bacterial infections that

barking on antimalarial treatment. In Nigeria a recent

7

may result in long term complications particularly in

younger children.

11

multicentre study conducted in 2009/2010 showed that

31

It

has been shown that urinary tract infection (UTI) is

Laboratory assessment

common in children presenting with febrile illness par-

ticularly in younger age groups, and could be associated

A

dipstick urinalysis was done on a portion of urine

12,13,14

with long-term complications.

These complications

specimen (catheter urine and clean catch for children 2

could be prevented by early diagnosis and prompt treat-

years and below, while mid-stream urine for older ones),

ment.

for

each subject who did not have any obvious focus of

infection. This was to identify the presence of nitrite and

Considering these, a systematic approach to case man-

or

leukocyte esterase (LE). Only the urine of children

agement of febrile children, particularly those under-five

whose dipstick urinalysis was positive for both nitrite

years is imperative. Such a measure would include care-

and LE or for either of the two were subjected to further

ful clinical evaluation and laboratory assessment to iden-

microbiological analysis according to National Institute

for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines.

16

tify the underlying cause of fever in each child. This

study was therefore, undertaken to highlight the underly-

The remaining portion of such urine sample was sent to

ing causes of fever in children six months to 59 months

the JUTH microbiology laboratory for microscopy, cul-

with specific emphasis on UTI identification in our hos-

ture and sensitivity within one hour of collection accord-

pital.

ing to standard protocol. The confirmation of UTI was

made only in children with a single bacterial isolate of

≥10 colony forming units (CFU) per ml of mid-stream

5

17

urine and 10 CFU/ml of catheter urine.

3

Materials and methods

Venous blood was obtained for peripheral smear and

subjected to Giemsa stain for

Plasmodium falciparum

This was prospective, cross-sectional and descriptive

identification and counting. Similarly, all children with

study, carried out in the paediatric emergency and outpa-

features suggestive of acute central nervous system in-

tient units of the Jos University Teaching Hospital, Ni-

fections (fever with seizures, nuchal rigidity or uncon-

geria. Study participants were children aged 6 to 59

sciousness) had lumbar punctures for cerebrospinal fluid

months seen in these units from the first of April to the

(CSF) analysis.

end of October 2012. Ethical approval was obtained

Data obtained were entered into EPI info version

from the Institution's Health Research and Ethics Com-

3.4.3software for analysis. The student‘t’ test was used

mittee. All children who presented with fever (axillary

to

compare group means and the Chi-squared test to

temperature ≥ 37.5 C), that had lasted less than two

o

compare proportions. Fisher exact was used when cells

weeks and whose parental/caregiver consent had been

contained observations less than 5. P value less than

obtained were consecutively recruited. Children with

0.05 was considered significant.

moderate to severe malnutrition according to world

health organization (WHO)

15

reference charts, those

with sickle cell anaemia or any underlying chronic ill-

nesses (renal, cardiac and chronic infection such as tu-

Results

berculosis or human immunosuppressive virus) were

excluded. Similarly, children who had used antibiotics

A

total of 303 children were recruited for the study. One

within one week prior to hospital visit were not in-

hundred and eighty (59.4%) were males while 123

cluded. All the children seen during the study, including

(40.6%) were females. Table 1 show the clinical charac-

those who participated and those who did not were

teristics of the subjects. The combined mean age for

given appropriate medical care following careful evalua-

both males and females was 21.67±14.02 while the me-

tion.

dian age was 17 months. One hundred and ninety nine

(65.7%) were aged less than 24 months.

Clinical assessment

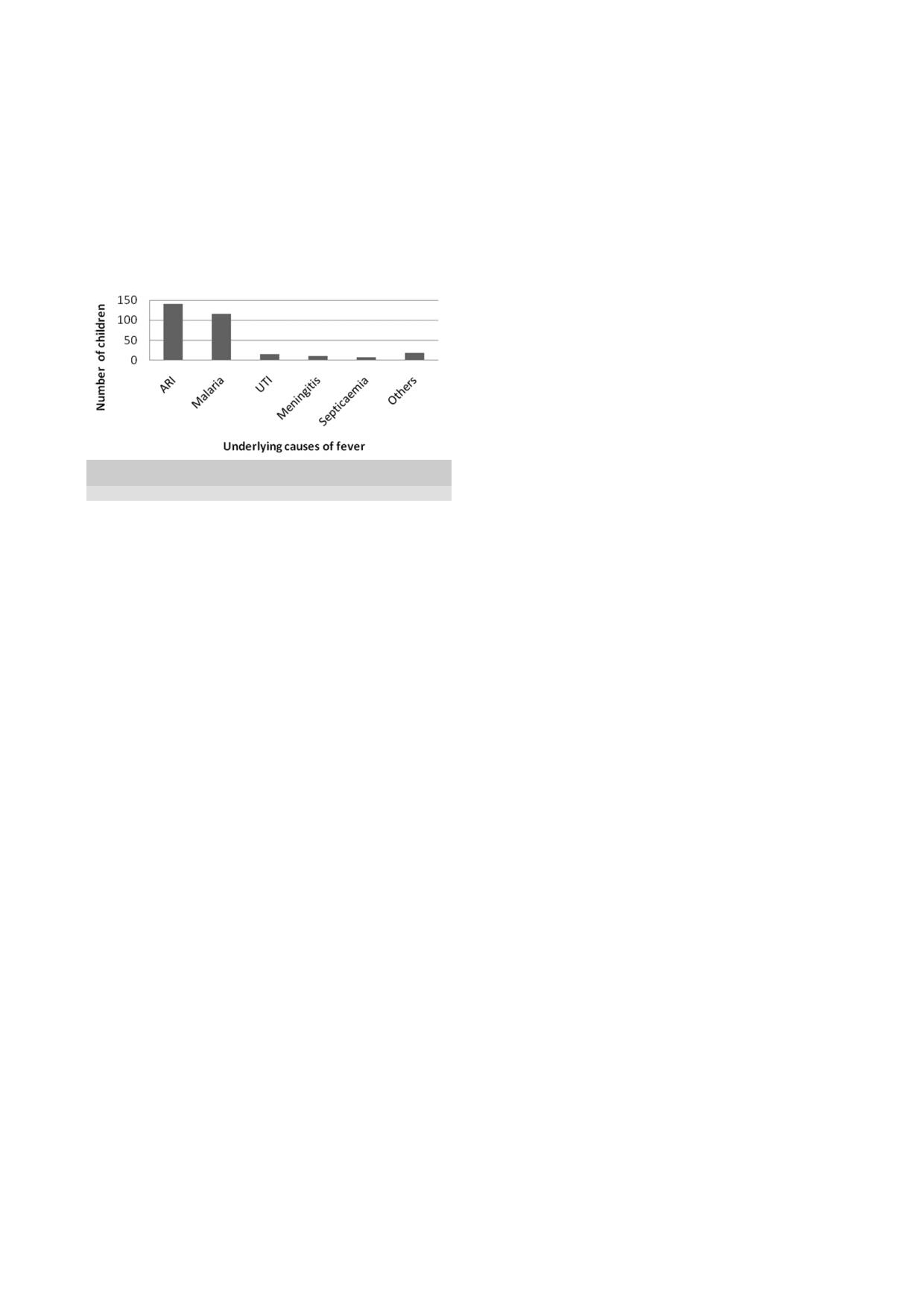

Fig 1 shows the causes of fever in the study population.

The history of illness was obtained from the patient’s

Acute respiratory infection, comprising tonsillitis, pneu-

parent/caregiver. Each child had physical examination to

monia and otitis media in that order, was the leading

identify possible focus of infection or any other feature

cause of fever in the children, constituting 44.6%. Ma-

that could assist in making diagnosis. Those who have

laria was the second common cause of fever followed by

clinical features suggestive of acute lower respiratory

urinary tract infection at 38.3% and 4.6% respectively.

infections had chest radiography. All participating sub-

Of

the children with ARI, 93 (69%) were aged 24

jects had their weight taken using a Seca® standing or

months and below with majority, 54 (58.1%) in this

bassinet weighing scales (infants), while height/length

group aged 12 months and less. Similarly, 86 (62.4%) of

was

measured in recumbent or standing positions based

the

children who had malaria were aged 24 months and

on

the age of the child respectively.

below. There were 14 children with UTI, 5(35.7%) in

The mid upper arm circumference (MUAC), was meas-

males and 9(64.3%) in females. Their mean age was

ured in all the children using an inelastic tape and meas-

25.4 ± 18.6 months. Eight children (57%) were 24

urement recorded to the nearest 0.1cm.

months or less while the remaining 6 (43%) patients

were older.

Three of the children with UTI also had parasitological

evidence of malaria. The commonest organism

32

responsible for UTI was

Escherichia coli in

8(57.1%).

graphical location may also have contributed as the find-

The other organisms included Klebsiella

species in 3

ing from Tanzania showed; the pattern of infection in

(21.4%), Staphylococcus

aureus 2(14.3%) and

Proteus

febrile children was different between the mainland and

species in 1(7.1%). A significantly high proportion

Zanzibar Island.

(86.4%) of the organisms isolated were sensitive to

flouroquinolones, sensitivity to gentamicin was 56.8%,

The prevalence of UTI in our study of 4.6% is much

while to the third generation cephalosporin (ceftriaxone)

lower than two previous and similar studies from other

parts of Nigeria.

22,23

Ibeneme et al

22

was 46.2%.

reported a UTI

prevalence of 11% in febrile children aged 1 to 59

Fig 1: Underlying

diagnosis of

fever in

the children

months in South East Nigeria. Their study included chil-

(Others- cellulitis, chicken pox, measles and mumps)

dren of much younger age than ours. It is known that the

prevalence of UTI is higher in younger infants, particu-

larly in the first few months of life.

12,14

Furthermore,

urine culture for microbiological confirmation of UTI

was done for all their study population without initial

screening for nitrite and LE, while we relied on positive

urine nitrite and/or LE for further urine culture. Conver-

sion of nitrate to nitrite does not occur with all bacteria

and it takes about 4 hours or more for conversion of

urine nitrate to nitrite in the bladder.

24

Therefore, if a

child had not retained urine for such period, it was pos-

Table 1: Characteristics

of the

study subjects

sible the screening will be falsely negative even where

Variable

Total

Male

Female

P

value

UTI was present. In their study from north western Ni-

Study population

303

180

123

-

geria, Wammanda et al

23

reported a UTI prevalence of

Age(months)

21.7 ±14.02

21.1 ±13.9

22.6 ±14.3

0.72

(Mean±SD)

24.3% in 185 febrile children who had symptoms refer-

Axillary Temp ( C)

o

38.2 ±0.78

38.2 ±0.76

38.2 ±0.81

0.73

able to the urogenital system. This figure is equally

(Mean±SD)

much higher than our finding. The higher rate they re-

Duration of fever

5.6±4.3

5.3±3.6

5.4±3.5

0.82

before presentation

ported is likely attributable to the fact that only those

(days) (Mean±SD)

children who had urinary signs and symptoms were re-

cruited. In that study, they also compared the ability of

positive urine nitrite to detect UTI with urine culture and

noted that nitrite was less sensitive but had an excellent

specificity. In other words, there is likelihood for this

23

Discussion

test

not to detect UTI even where infection is present.

From

our study, acute respiratory infection was identi-

fied

as the leading infection in children presenting with

Our

study evaluated children for UTI only if they had no

fever, followed by malaria. Urinary tract infection was

focus of infection and where preliminary screening for

the third common cause of fever in these children. This

nitrite and LE was positive. It has been shown that nei-

general pattern is similar to findings from other studies

ther

absence nor presence of a focus of infection neces-

sarily affects the existence of UTI in children. This may

14

in

Africa and elsewhere in the world.

18,19,20,21

In

a study

of

418 children with fever in Gabon, Bouyou-Akotet et

have contributed to the lower prevalence rate observed

al

reported UTI prevalence of 4.1%, while D’Acre-

18

in

this study.

mont et al , in his review of the causes of fever in 1005

19

The prevalence of UTI in febrile children in our study

Tanzanian (Zanzibar) children 2 months to 10 years re-

may have come in a distant third position, but it empha-

ported a prevalence of 5.9%. These studies also showed

sise a significant point that this condition is to be looked

that acute respiratory infection was the commonest

for in children presenting with fever when there is no

cause of fever in the children as our study demonstrated.

focus of infection. This is more so that managing the

We

found that malaria was the second most common

long term complications associated with renal scarring

cause of fever similar to the report from Gabon,

18

but

from pyelonephritis is much more challenging and diffi-

this contrasts with the observation from Zanzibar

19

cult in our environment.

where malaria was the fourth common cause of fever.

Our study has some limitations: urine culture was car-

This variation may be related to capacities for further

ried out only in children whose dipstick urinalysis was

laboratory investigations, environmental and weather

positive for nitrite and/or LE. There may have been

conditions. For instance, in mainland Tanzania, the com-

some of these children whose dipstick urinalysis was

monest cause of fever among 870 paediatric and adult

negative for nitrite and LE but who may actually have

patients was bacterial zoonoses while malaria was re-

UTI. However, this study has shown that, for children

sponsible in only 1.6%. Similarly, among 1180 hospi-

20

presenting with fever in our environment, acute respira-

talized Cambodian children under 8 years with 1225

tory infection is the commonest condition, followed by

febrile episodes, Chheng et al reported that acute respi-

21

malaria and then UTI, stressing the need to evaluate

ratory infection was the foremost cause of fever fol-

such children with this order in mind.

lowed by different kinds of viral infections. The geo-

33

Acknowledgments

Mrs Carol Okorie for carefully analysing the entire

blood specimen for malaria parasites for the children.

We

are grateful to all the children and their parents that

participated in this study. We also acknowledge

Conflict of interest: None

Funding: None

References

1.

Kallander K, Nsungwa-Sabiiti J,

9.

Roll Back Malaria. World malaria

18.

Duguid JP, Marmaion BP, Swain

RH.

Medical Microbiology. 13

th

Peterson S. Symptom overlaps for

report. 2005. http://www.rollback

malaria and pneumonia-policy

malaria.org/wmr2005.

ed.

Edinburgh: Churchill

Living-

implications for home manage-

10.

O'Meara WP, Bejon P, Mwangi

stone; 1978. p. 327-33

ment strategies. Acta

Trop.

TW,

Okiro EA, Peshu N, Snow

19.

Bouyou-Akotet MK, Mawili-

2004;70:211 – 214.

RW,

Newton CRJC, Marsh K.

Mboumba DP, Kendjo E, Ekoum

2.

Liu

L, Johnson HL, Cousens

Effect of a fall in malaria transmis-

AE,

AbdouRaouf O, Allogho EE

S,Perin J, Scott S, et al. Global,

sion on morbidity and mortality in

et

al. Complicated malaria and

regional, and national causes of

Kilifi, Kenya. Lancet.

2008; 70:

other severe febrile illness in a

child mortality: an updated sys-

1555 – 1562

pediatric ward in Libreville, Ga-

tematic analysis for 2010 with

11.

Guerra CA, Gikandi PW, Tatem

bon. Infect

Dis 2012;

12:216-225.

time trends since 2000. Lancet

AJ,

Noor AM, Smith DL, Hay SI,

20.

D’Acremont V, Kilowoko M,

2012; 379: 2151 – 2161

Snow RW. The limits and intensity

Kyungu E, Philipina S, Sangu W,

3.

Rougemont A, Breslow N, Bren-

of Plasmodium falciparum

trans-

Kahama-Maro J et al. Beyond ma-

ner

E, Moret AL, Dumbo O, Dolo

mission :

implications for

malaria

laria — causes of fever in outpatient

A,

Soula G, Perrin L. Epidemiol-

control and elimination worldwide.

Tanzanian children. N

Engl J

Med

ogical basis for clinical diagnosis

PLoS Med. 2008;70:e38. doi:

2014; 370:809-817.

of

childhood malaria in endemic

10.1371/journal.pmed.0050038.

21.

Wolter N, Cohen C, von Gottberg

zone in West Africa. Lancet

12.

Lin DS, Huang SH, Lin CC, Tung

A.

Causes of fever in outpatient

1991;70:1292 – 1295

YC,

Huang TT, Chiu NC et al.

Tanzanian children. N

Engl J

Med

4.

Akpede G.O. and Skyes R.M.

Urinary tract infection in febrile

2014;370(23):2243-2248.

(1992) Relative contribution of

infants younger than eight weeks

22.

Chheng K, Carter MJ, Emary K,

bacteremia and malaria to acute

of

age. Pediatrics

2000;105:E20

Chanpheaktra N, Moore CE,

fever without localizing signs of

13.

Crain EF, Gershel JC. Urinary

Stoesser N et al. A prospective

infections in under five children.

J

tract infection in febrile infants

study of the causes of febrile ill-

Trop Pediatr38, 295-298.

younger than eight weeks of age.

ness requiring hospitalization in

5.

English M., Reyburn H., Good-

Pediatrics 1990; 86:363-367.

children in Cambodia. PLoS

One

man

C. and Snow R.W. (2009)

14.

O’Brien K, Edwards A, Hood K,

2013;8(4): e60634.

Abandoning presumptive antima-

Butler CC. Prevalence of urinary

23.

Ibeneme CA, Oguonu T, Okafor

larial treat-ment for febrile chil-

tract infection in acutely unwell

HU,

Ikefuna AN, Ozumba UC.

dren aged less than five years- a

children in general practice: a pro-

Urinary tract infection in febrile

case of running before we can

spective study with systematic

under five children in Enugu,

walk? PLoS

Med 6, e1000015.

urine sampling. Br

J Gen

Pract

South Eastern Nigeria. Niger J

Clin

6.

D’Acremont V, Lengeler C, Gen-

2013;

63(607):156-164.

Pract 2014;17:624-628.

ton

B. Reduction in the proportion

15.

World Health Organisation, UNI-

24.

Wammanda RD, Aikhionbare HA,

of

fevers associated with Plasmo-

CEF. WHO growth standards and

Ogala WN. Use of nitrite dipstick

dium falciparum parasitaemia in

the

identification of severe acute

test in the screening for urinary

Africa: a systematic review.

Malar

malnutrition in infants and chil-

tract infection in children. West Afr

J 2010;9:240-249.

dren. A joint statement by the

J Med 2000; 19: 206-208.

7.

Gething PW, Patil AP, Smith DL,

World Health Organisation and the

25.

Jodal U. Urinary tract infection:

Guerra CA, Elyazar RF, Johnston

United Nations Children's Fund.

significance, pathogenesis, clinical

GL

et al. A new world malarial

Geneva: WHO, 2009.

features and diagnosis. In: Pos-

map: Plasmodium falciparum

URL:www.who.int/nutrition/

tlethwaite RJ, editor. Clinical Pae-

endemicity in 2010. Malar

J

publications/severemal nutri-

diatric Nephrology. Oxford: But-

2011; 10: 378-386.

tion/9789241598163/en/index.html

terworth - Heinemann; 1994. pp.

8.

Oguche S, Okafor HU, Watila I,

(accessed 21 May 2012).

151

– 9.

Meremiku M, Agomo P, Ogala W

16.

National Institute for Health and

et

al. Efficacy of Artemisinin-

Care Excellence (NICE). Urinary

Based Combination Treatments of

tract infection in children. 2007.

Uncomplicated Falciparum Ma-

http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG05.

laria in Under-Five-Year-Old Ni-

gerian Children. Am.

J. Trop.

Med.

Hyg., 91(5), 2014, pp. 925 – 935